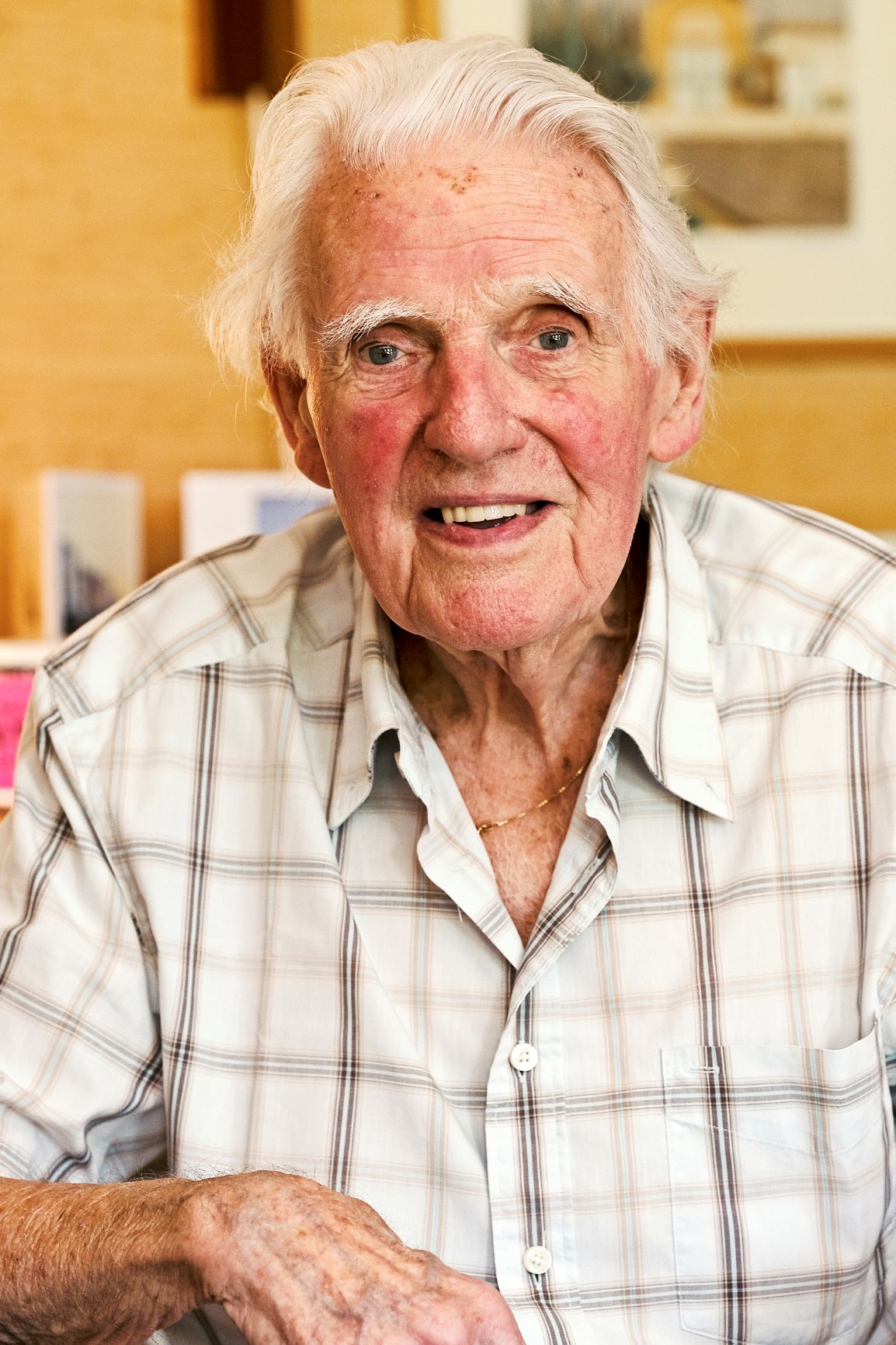

My fascination with buildings began at a young age. As my drawing skills developed so did my interest in the magnificent warehouses in and around Manchester – my home and birthplace in 1927. The start of my teenage years coincided with World War Two and the systematic aerial bombardment of Manchester. Our home, heavily damaged during a raid, became uninhabitable – moving in with my grandparents on the other side of town was our only option. Despite the turmoil I continued my grammar school education. A catalogue presented to me by a teacher, which included the emerging concept of new towns, sparked my interest yet further.

My fascination with buildings began at a young age. As my drawing skills developed so did my interest in the magnificent warehouses in and around Manchester – my home and birthplace in 1927. The start of my teenage years coincided with World War Two and the systematic aerial bombardment of Manchester. Our home, heavily damaged during a raid, became uninhabitable – moving in with my grandparents on the other side of town was our only option. Despite the turmoil I continued my grammar school education. A catalogue presented to me by a teacher, which included the emerging concept of new towns, sparked my interest yet further.

Even before war ravaged many of Britain’s cities, it was self-evident that antiquated living conditions needed addressing. As tragic as it was, war became the catalyst to put plans into action – modern, purpose-built towns were the way forward. I wanted to be part of this exciting future; I knew that building was going to be a priority for a postwar Britain. Therefore, at the age of seventeen I started at Manchester University School of Architecture, where we crafted detailed building designs of all types. The whole process of designing within the context of your environment came naturally to me – an ideal basis for ‘new town’ planning.

However, I knew that as I approached eighteen it meant one thing – army conscription. World War Two, at least in Europe, was over. Nonetheless, there was a place for me within the Royal Engineers in Germany. Initially, I regarded the three years in the army as a hindrance to my education, in hindsight I now see how I matured. Where else would someone like myself, who prior to enlistment hadn’t been to London let alone Europe, have had the opportunity to experience different cultures and cities. I even got to visit Paris – which, unlike other European cities, was largely intact. Consequently I got more from the remaining four years at university and completed my degree with first-class honours.

'I made up my mind that I wanted to work for him and on the creation of Harlow New Town'

While I was at university the New Towns Act was passed by parliament. It decreed that eight new towns (in total accommodating up to 500,000 people) be built within fifty miles of London. In 1947 architect Frederick Gibberd announced his eagerly awaited master plan for Harlow New Town. His vision, unlike Corbusier’s, wasn’t just high-rise buildings. Instead his priority was giving people what they wanted: homes with gardens, amid green spaces and community infrastructure which above all respected and complemented the surrounding landscape.

An opportunity to attend a lecture by Gibberd, in which he discussed his plans for Harlow, was something I couldn’t afford to miss. When the moment came I asked whether I too would have an opportunity to design buildings if I ever came to work in Harlow. ‘Yes,’ was his reply. The town urgently needed cutting-edge architecture of every conceivable type. There and then I made up my mind that I wanted to work for him and on the creation of Harlow New Town.

The newly established Harlow Development Corporation (HDC) was responsible for the management, design and development of the town – with finance coming from Treasury loans and the power to compulsorily purchase land. However, one thing they couldn’t have in its entirety was Gibberd. He wasn’t about to forgo his already well-established architectural practice in London. Instead he was given the role of Consultant Architect and Planner – in other words, the visionary – with an executive architect overseeing day-to-day running. In 1952, after spotting an advertisement, I was interviewed for the role of temporary assistant architect in Harlow. This wasn’t my first trip to Harlow: I’d made two previous visits, once as a student and the other on my way back from the Festival of Britain in 1951 – inspiration to myself and countless other architects. Having secured the job and proved my worth, it later led to a permanent position.

One of my early projects for HDC was a small group of shops on Edinburgh Way; which still exists. After spending a year on an architectural scholarship in Rome I returned to HDC. During this time I worked on the design of Market Square – notably the building many refer to as the ‘Clock House’, which originally had a sheltered walkway or colonnade.

Gibberd visited Harlow once maybe twice a week to work with architects and planners. His belief in the town was such that he bought a house and garden at the end of Marsh Lane and opened a branch office in the town centre. This became my place of work when I joined as assistant architect, and in later years I became an associate then partner. In total I was there for twenty-seven years.

Aside from my involvement in the sports centre and the Harvey Centre, I also designed the original town hall gallery space, with commanding views of Harlow atop the town hall. I drew upon Mediterranean influences, incorporating barrel vaults and an exterior clad in shimmering white glass mosaic. I worked closely with Gibberd on the offices for the publishers Longmans Green (once opposite the station) – arguably his best building in Harlow.

Sadly several of these key buildings have been demolished. In 1980 the government wanted development in Harlow to stop. The Treasury sold off the HDC’s land and took ownership of their most lucrative assets – leaving the council with the housing. Such actions had a massive impact on the town. Planning a town’s future without land to develop, and with available land in private hands, is well-nigh impossible.

'I'm a perennial idealist'

Myself and the three other partners in the Gibberd office knew work would dry up. Therefore, against my wishes, their plan was to relocate to London. I didn’t want to live in Harlow and commute to London – that was the opposite of the new town ideal. Therefore I resigned, took over the lease of the Harlow office and ran it as a modern art gallery for three years, but that is another story.

As an architect every building you design is a high point. Therefore, witnessing its destruction or ill-conceived alteration is hurtful. I’m sometimes asked what it feels like to live in Harlow after the era of the HDC – ‘Painful’ is my reply. The development of Harlow has been largely stagnant since 1980 – we never got to see the full plans of Gibberd. We were once at the forefront of modern town planning; an inspiration to architects and planners around the world.

Plans are afoot for Harlow’s expansion. My hope is that we can sidestep developers, whose motivations are pleasing shareholders rather than the community itself. First and foremost the present state of the town centre needs addressing, before we build yet further housing.

Despite being in my ninetieth year, I cannot keep my silence if made aware of something which is detrimental to the town. I owe it to Harlow and Sir Frederick Gibberd, a complex and at times shy man that I knew as a friend. Yes, Harlow has changed but I’ve never thought about moving – so much of my life has revolved around Harlow. Which, for a large part, is still a great place to live. I guess I’m a perennial idealist.