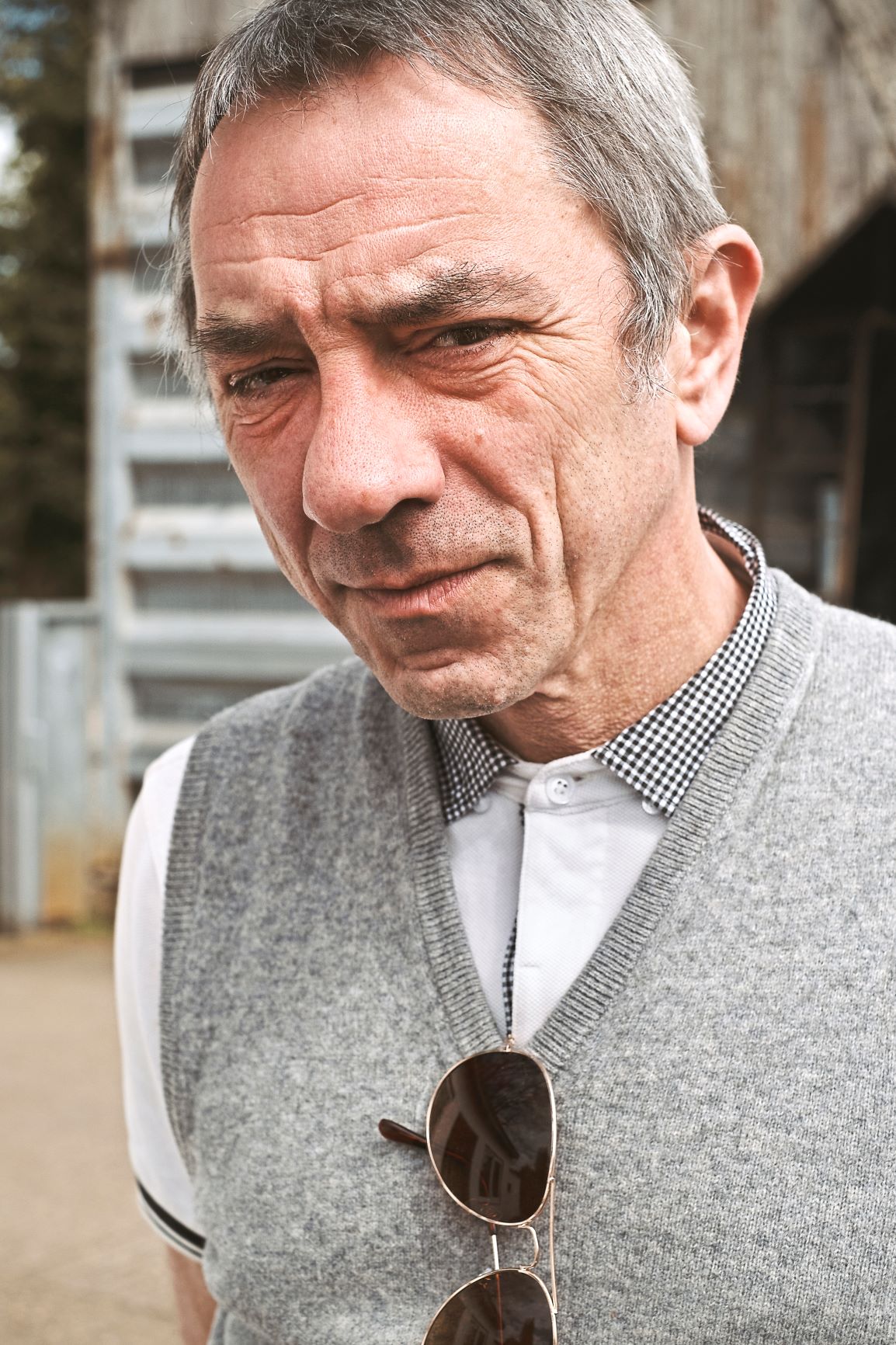

Despite growing up in leafy Woodford, my family roots are deeply entrenched in the East End of London; primarily Bethnal Green. I was born not only inheriting the name Edward, but in line to follow in the footsteps of my father – a bookmaker. However, by the time I reached the age of eight my parents deemed there would be no real future in that career. So in a break with tradition (bookies in my family going back to the 1860s) I was farmed out to boarding school, paving the way for my ‘so-called’ gentrification. As the years ticked by so did suggestions as to potential careers I might follow. My parents’ efforts were all in vain; little more than white noise. As far as I was concerned a white-collar existence wasn’t for me – my mind was firmly set on a career within the music industry. And rightly so, things were already taking shape by the time I’d left school. A mod fanzine called Extraordinary Sensations that I established in 1980 aged sixteen was selling 10,000 copies by the time I reached my seventeenth birthday.

Despite growing up in leafy Woodford, my family roots are deeply entrenched in the East End of London; primarily Bethnal Green. I was born not only inheriting the name Edward, but in line to follow in the footsteps of my father – a bookmaker. However, by the time I reached the age of eight my parents deemed there would be no real future in that career. So in a break with tradition (bookies in my family going back to the 1860s) I was farmed out to boarding school, paving the way for my ‘so-called’ gentrification. As the years ticked by so did suggestions as to potential careers I might follow. My parents’ efforts were all in vain; little more than white noise. As far as I was concerned a white-collar existence wasn’t for me – my mind was firmly set on a career within the music industry. And rightly so, things were already taking shape by the time I’d left school. A mod fanzine called Extraordinary Sensations that I established in 1980 aged sixteen was selling 10,000 copies by the time I reached my seventeenth birthday.

'more luck than judgement'

However, the route to my first job relied more on luck than judgement – something that would become prevalent over the subsequent years. I was on a train returning home after a Purple Hearts gig. Idle chatter with a fellow mod turned to the fact that he worked at the Labour Exchange on Wardour Street, London. As luck would have it, I knew that was a location where a cluster of record companies often advertised vacancies. Securing such a prized job was more a case of ‘first come first served’. Therefore, to circumvent the system I gave him a fiver – a lot of money back then – on the proviso that he’d tip me off regarding any record company jobs before they were pinned to the wall and advertised to the masses. It proved a canny investment when several weeks later I bagged a job as motorcycle messenger at a record company called Avatar. The job gave me industry experience, but did it underline that Lambrettas (using one day in, day out) are shocking scooters! A bone of contention, I know – but it’s why I now ride a Vespa. From Avatar I moved to Stiff Records and by eighteen, among other things, I’d set up my own record label. In the 90s I signed the likes of Jamiroquai, Brand New Heavies, Snowboy, to name but a few, to the Acid Jazz record label which I co-founded with DJ Gilles Peterson. To this day I’m still heavily involved in the music – DJ’ing around the world and broadcasting. I’ve been very fortunate and this is but a tiny snapshot of my life, with highs and lows along the way.

As for early encounters with Harlow, well they came about in the early 80s while managing an R‘n’B mod band called Fast Eddie – with Benny’s Nightclub being a venue where I’d occasionally put a gig on. The town was already influential in music, having pioneered a host of influential mod, ska and punk bands.

'you can't just put everything back in the box and make it 1974 again'

I was drawn towards living in Harlow based on the concept it was founded on. When the idea of ‘new towns’ was conceived, first and foremost it was about community; in the case of Harlow, a network of villages connected around an urban centre with an array of recreational facilities. Having now lived here for twenty-one years I’ve seen the decline and removal of those ideals – particularly in the last fifteen years. Sadly, a majority of what this town once prided itself on has gone, facilities either disappearing through a lack of funding or rapaciously replaced with cheap ill-conceived housing estates.

I’ve witnessed the closing of facilities that directly affect the developing minds of our younger generation. From my forty years’ experience working in the culture industry I know that children with no facilities have a higher propensity to become ‘disengaged’ children – it’s quite simple; it’s not rocket science. The parallels between the two junctures (facility closure and community strife) are evident. I wish it were different, but you can’t just put everything back in the box and make it 1974 again.

That said, I’m proud of the town and my views are based upon the fact I care about Harlow. A real moment for me, a glimmer of hope for the town’s future, was the way that elements of the town came together around the campaign to save The Square. It showed me that there is an interest – a genuine interest – for proper culture in the town. People would stop me in the town or holler their support from across the street. With such a showing of strength I really thought it was going to be saved, but fundamentally we are powerless against opportunistic developers. This was something I experienced first-hand when The Blue Note (a club I opened in Hoxton Square) was closed over spurious claims and redeveloped when Hoxton became the fashionable place to be.

We are often short-sighted and don’t realise what we have until it’s gone.