My grandparents, originally from Ireland, came to Harlow in 1958. Soon after my mother came over to join them and that’s where she met and married my father – a Glaswegian builder. My early childhood was good – the town had plenty of things for me to do – but having been born with a club foot I knew my limitations. I went through untold operations to rectify the abnormality and for many years had metal callipers and a built-up shoe. Of course, kids being kids, I bore the brunt of mild banter over my foot; but I never took offence. However, I couldn’t help wishing things were different as I watched my mates climb trees or, from my usual vantage point as goalie, witnessed their football skills develop.

My grandparents, originally from Ireland, came to Harlow in 1958. Soon after my mother came over to join them and that’s where she met and married my father – a Glaswegian builder. My early childhood was good – the town had plenty of things for me to do – but having been born with a club foot I knew my limitations. I went through untold operations to rectify the abnormality and for many years had metal callipers and a built-up shoe. Of course, kids being kids, I bore the brunt of mild banter over my foot; but I never took offence. However, I couldn’t help wishing things were different as I watched my mates climb trees or, from my usual vantage point as goalie, witnessed their football skills develop.

As I grew older an altogether different battle unfolded. My father was deeply violent towards my mother, myself and seven siblings – I was petrified of the man. If I tried to intervene during one of his all too frequent rages I’d become his target – he’d hit me not as a child, but an adult. At times, when I could no longer sit idly by, I’d climb from my first-floor bedroom window, onto the porch, down the drainpipe and sprint to the phone box – where I’d call the police before hastily returning to my room. Unfortunately, when they arrived my father (well known to the police) would play it down as a minor domestic and they’d be on their way. Then, regardless of who actually made the call, we’d all be on the receiving end of his anger – but this was still the lesser of two evils, as it gave my mother some respite.

'...he'd created his own monster'

Many will ask why my mother just didn’t leave. But with eight children (each a year apart) my mother, like us all, was trapped. Whenever she did escape the overwhelming guilt over not being there for us meant she’d soon return. Any outside help we received was next to useless. The one and only time I confided in someone (a school friend) it set me into panic mode, when I made the connection that our fathers knew each other – what if word had gotten out over what I’d divulged? Next day, consumed with fear, I played down the situation with my friend – putting it down as a sick joke I’d played on him.

My time at secondary school was a nightmare – ultimately I got thrown out aged fifteen. My father, keen to get shot of me while he went down the pub, enrolled me at a boxing club. I was good; but inadvertently he’d created his own monster. Years later I turned professional, but even when I ultimately messed that up (indulging in drink and drugs) I still got plenty of action: through being a doorman, unlicensed boxing and pub brawls.

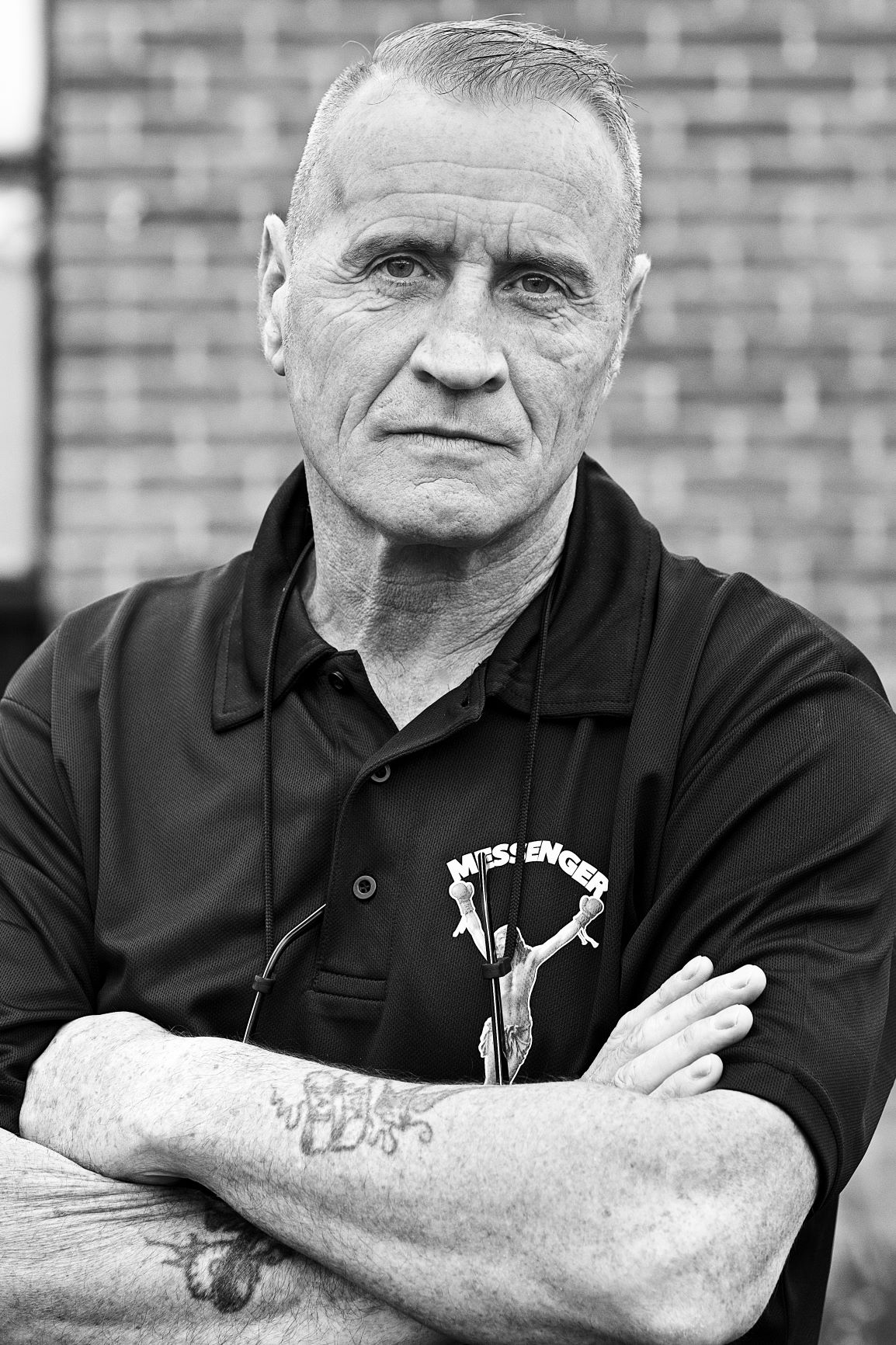

I really struggled to deal with my demons and became a very selfish man. Even though I had a good heart, it became overshadowed by all the bad stuff I was doing. I’d listen to other people’s troubles and make all the right noises – but my real empathy towards others was almost nonexistent, as in the back of my mind I couldn’t care less. For all the wrong reasons I became a ‘name’ around town and I played up to the notoriety – if ever there was an altercation I was up for a fight, as whatever anyone dished out was nothing to what I’d endured as a kid. When visiting a club or pub it was free drinks all night, but what I didn’t pay for then I certainly paid for later in life. In retrospect I can see that I wasn’t living, just existing. But what sickened me most was that I’d emulated my father and become everything I hated about him – even a simple tattoo dedicated to my mother had to be adorned with his name; that was the hold he had over me. I became a thorn in my mother’s side; the things I did broke her heart. But regardless, she’d defend and protect me to the nth degree – probably, even though she had no reason to, feeling guilty for who I’d become.

'I set about making amends ... doing something positive for Harlow'

In my twenties my pent-up anger got the better of me. I went to my father’s house and coaxed him outside by putting a few bricks through his window. The brawl, giving him as good as he’d given to my mother, myself and my siblings, resulted in my arrest. I was subsequently charged with GBH – if he’d died of his injuries within a year and a day I’d have been back before them on a murder charge. I’ll be honest – I was praying that would be the case. From that day forward I had nothing further to do with him.

By 2015, after many ups and downs I had calmed down a lot. However, in June of that year I felt the sharpest of pains in my head – I was having a stroke, aneurysm and cardiac arrest – moments later I collapsed. The warning signs had been there, dull headaches that I’d put down to the hot weather that week. Despite my wife’s quick reactions, technically I was dead for six minutes. Upon hearing the news about her prodigal son, my mother (still in possession of her dark Irish humour) said, ‘You can’t kill a bad thing!’.

When I finally left hospital, my speech was impaired, my memory full of holes and I couldn’t walk without a frame. But I’d gained something far more important – a purpose in life. I’ve never been religious, but while in hospital I had what can best be described as a visit – an intervention if you like. It got me thinking: around me (in intensive care) there were others – good people with the same problems, doctors and treatment – who didn’t pull through. And there was me, by rights someone who didn’t deserve to walk this earth, surviving – how does that work? One thing I did know was that my life had to change. Without that intervention I’d likely have gone back to my old chaotic ways. This time, having survived against all odds, I had a new level of invincibility.

My life expectancy has almost certainly been reduced, but even if that wasn’t the case I still wouldn’t have the time to apologise to everyone I’ve hurt over the years. Therefore, after my long rehabilitation, I set about making amends for what I’ve done – part of which was doing something positive for Harlow. In 2017 I established a community drop-in centre, where the homeless or those in need of companionship can have a hot meal and a chat. Ultimately it helps disengaged members of the community feel they’ve a place in society – including the troubled kids around town who’ve become the focus of much attention. I’m going to give it my all and help them avoid the mistakes I’ve made in life. I’ve had nothing but encouragement for what I’m doing and, because I’m unable to work (funding the initiative with my own money), I’ve received generous donations from many good folk in Harlow.

As you might expect, I’ve a love-hate relationship with the town; nevertheless, I’m glad to be living here and at least now effecting change in a good way.

I’ve finally got peace in my life, and no one is happier about that than my mother. She’s in her eighties now, so I’m just glad she’s had the opportunity to witness my change – a chapter in her life with a happy ending.