With my ‘business head’ on I’m not entirely sure how much longer it’s going to be viable for me to operate the stall. My heart’s still in the job – I can’t switch off a way of life that’s been instilled in me from a young age. But from a personal perspective I can’t leave it until the wage I depend upon dries up and causes me financial problems. Fingers crossed that day is way off; but if such a decision was made it would require careful timing, primarily because I’d need sufficient time to diversify the business or seek employment. Closing would be a double whammy, not just for myself, but the business legacy that my father and grandfather grew from nothing.

With my ‘business head’ on I’m not entirely sure how much longer it’s going to be viable for me to operate the stall. My heart’s still in the job – I can’t switch off a way of life that’s been instilled in me from a young age. But from a personal perspective I can’t leave it until the wage I depend upon dries up and causes me financial problems. Fingers crossed that day is way off; but if such a decision was made it would require careful timing, primarily because I’d need sufficient time to diversify the business or seek employment. Closing would be a double whammy, not just for myself, but the business legacy that my father and grandfather grew from nothing.

My grandfather came to England in the early 1970s. Prior to that he’d spent several years in Frankfurt – the city he chose to settle in having left his home country of India. His decision to leave was something he didn’t take lightly. Firstly, he’d left his wife and children behind; secondly, it was to move to a country whose culture was alien to him. The driving force behind his decision to leave India was to earn a wage and send money home to support his family. Initially he had a very tough time. He spared us most of the details – I guess he didn’t want to cause us upset over what he’d endured. What little we do know is that, penniless, he often slept rough on park benches. And, despite being a moderately religious Hindu, he’d forego his strict vegetarian diet just to survive the harsh German winters.

'My wages of a burger and fizzy drink were more than enough'

Much like in Germany, my grandfather had his share of problems upon arriving in England. But after long hours and hard graft he found his feet. His reward? Deportation back to India. It was in his nature to work hard and prove his worth. However, by doing so it exposed his lazy co-workers who, when noticing that he was earning more, took it upon themselves to report him to the authorities. You see, my grandfather had overstayed his allotted time in the UK. His next visit to England was all above board which, after years of being an exemplary character, led to citizenship. Only when he’d bought a house and was financially secure did his wife and children (my father included) join him.

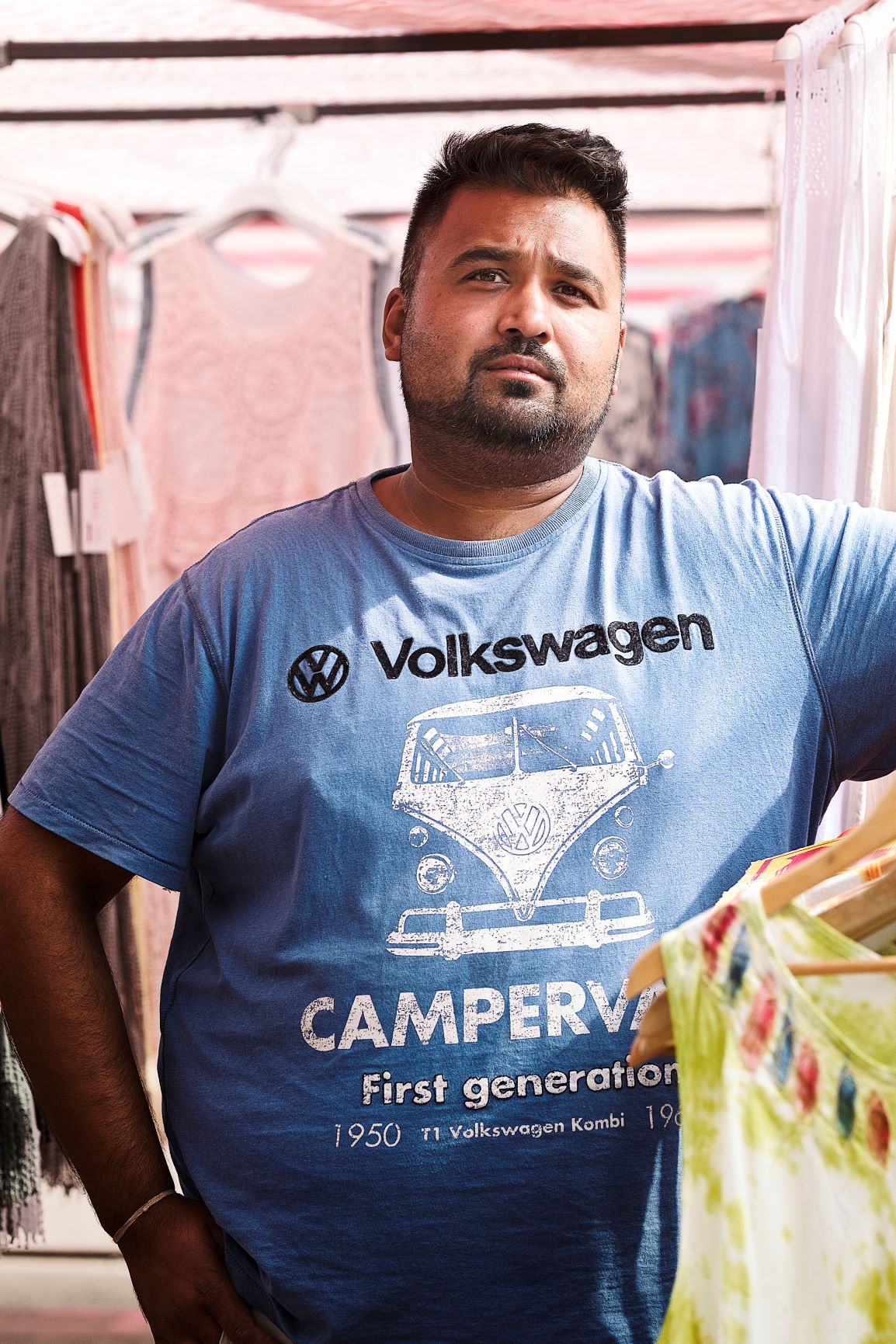

I was born in 1982, by which point my father had been working in a clothing factory for some time. Back then, unlike today, the British clothing industry was strong and well rooted into communities across the East End of London. It created work opportunities for stay-at-home mothers (like my own), who stitched garments in their spare time. Seeing an opportunity, my father and grandfather set up their own factory – which at its peak employed over a hundred people.

The fashion industry then was a far cry from what we know today. Much of the clothing my family’s business manufactured, aside from a slight pattern or fabric change, didn’t alter in years. We’d produce and push out a thousand pieces without even second-guessing ourselves – we knew it would sell.

As fashion trends changed we aimed our styles at a more youthful generation. This coincided in the early 90s with the onset of fast fashion and a slump in UK manufacturing. A few years later, when it became cheaper to import clothing from the other side of the world, many factories went bust – along with the livelihoods of hundreds in already deprived areas. By the turn of the millennium my family’s business was faced with just that problem – they couldn’t compete with prices from overseas. This was the catalyst for my father and grandfather to call it a day and revert fully to market stalls, which incidentally is how their business had grown from the start. I’d been cutting my teeth on market stalls from the age of six. The day started with my father waking me at some ungodly hour before putting me in the van and heading off to an outdoor market and setting up the stall. For me it was a good fun outing, I enjoyed the action – my wages of a burger and fizzy drink were more than enough.

In the mid-90s, when I started on this stall, Harlow was an altogether different place. The town centre had a good atmosphere – especially in the market. However, it wasn’t – how can I put it? – at the cutting edge of fashion. The town still had a large proportion of the ‘make do and mend’ generation, whose preference was simpler fashions at the right price. Sadly a majority of that generation has now passed on, and with that the age range and cultural mix of the town has changed. We now stock more varied styles to cater for different fashion tastes.

The people may have changed – but, by the same token the council sometimes haven’t helped prevent the downfall of the town centre. The opening of the Water Gardens and a lack of impetus in driving trade towards the market created a division between old and new. The trust and customer service that myself and others built up over the years wasn’t enough to retain our customers – the closure of many retail outlets was inevitable.

'...it felt good when the people of Harlow remarked how they'd miss me'

I like to think I’ve good judgement when it comes to knowing what will or won’t sell. But if for whatever reason something doesn’t shift I won’t sell it at a loss. I’ll put those items aside and when I’ve got a few bags together I’ll donate them to a nearby charity shop.

Not long ago I didn’t see a future in what I was doing, so I packed it in and tried a different line of work – sadly that didn’t work out. But during those eight months I found out how much I missed working on the stall. Thank goodness I had that trade to fall back on and it felt good when I returned and the people of Harlow remarked how they’d missed me.